The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

| The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring | |

|---|---|

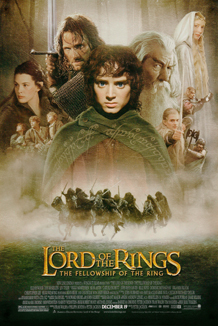

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Jackson |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Fellowship of the Ring by J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Andrew Lesnie |

| Edited by | John Gilbert |

| Music by | Howard Shore |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 178 minutes[2] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $93 million[3] |

| Box office | $887.4 million[4] |

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring is a 2001 epic high fantasy adventure film directed by Peter Jackson from a screenplay by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, and Jackson, based on 1954's The Fellowship of the Ring, the first volume of the novel The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien. The film is the first instalment in The Lord of the Rings trilogy. It features an ensemble cast including Elijah Wood, Ian McKellen, Liv Tyler, Viggo Mortensen, Sean Astin, Cate Blanchett, John Rhys-Davies, Billy Boyd, Dominic Monaghan, Orlando Bloom, Christopher Lee, Hugo Weaving, Sean Bean, Ian Holm, and Andy Serkis.

Set in Middle-earth, the story tells of the Dark Lord Sauron, who seeks the One Ring, which contains part of his might, to return to power. The Ring has found its way to the young hobbit Frodo Baggins. The fate of Middle-earth hangs in the balance as Frodo and eight companions (who form the Company of the Ring) begin their perilous journey to Mount Doom in the land of Mordor, the only place where the Ring can be destroyed. The Fellowship of the Ring was financed and distributed by American studio New Line Cinema, but filmed and edited entirely in Jackson's native New Zealand, concurrently with the other two parts of the trilogy.

It was premiered on 10 December 2001 at the Odeon Leicester Square in London and released on 19 December in the United States and on 20 December in New Zealand. The film was acclaimed by critics and fans alike, who considered it a landmark in filmmaking and an achievement in the fantasy film genre. It received praise for its visual effects, performances, Jackson's direction, screenplay, musical score, and faithfulness to the source material. It grossed over $868 million worldwide during its original theatrical run, making it the second-highest-grossing film of 2001 and the fifth- highest-grossing film of all time at the time of its release.[5] Following subsequent reissues, it has grossed over $887 million.[4] Like its successors, The Fellowship of the Ring is widely recognised as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made. The film received numerous accolades; at the 74th Academy Awards, it was nominated for thirteen awards, including Best Picture, winning for Best Cinematography, Best Makeup, Best Original Score, and Best Visual Effects.

In 2007, the American Film Institute named it one of the 100 greatest American films in history, being both the most recent film and the only film released in the 21st century to make it to the list. In 2021, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[6] Two sequels, The Two Towers and The Return of the King, followed in 2002 and 2003, respectively.

Plot

[edit]In the Second Age of Middle-earth, the lords of Elves, Dwarves, and Men are given Rings of Power. Unbeknownst to them, the Dark Lord Sauron forges the One Ring in Mount Doom, instilling into it a great part of his power to dominate the other Rings and conquer Middle-earth. A final alliance of Men and Elves battles Sauron's forces in Mordor. Isildur of Gondor severs Sauron's finger and the Ring with it, thereby vanquishing Sauron and returning him to spirit form. With Sauron's first defeat, the Third Age of Middle-earth begins. The Ring's influence corrupts Isildur, who takes it for himself and is later killed by Orcs. The Ring is lost in a river for 2,500 years until it is found by Gollum, who owns it for over four and a half centuries. The Ring abandons Gollum and is subsequently found by a hobbit named Bilbo Baggins, who is unaware of its history.

Sixty years later, Bilbo celebrates his 111th birthday in the Shire, reuniting with his old friend, the wizard Gandalf the Grey. Bilbo departs the Shire for one last adventure and leaves his inheritance, including the Ring, to his nephew Frodo. Gandalf investigates the Ring, discovers its true nature, and learns that Gollum was captured and tortured by Sauron's Orcs, revealing two words during his interrogation: "Shire" and "Baggins." Gandalf returns and warns Frodo to leave the Shire. As Frodo departs with his friend, gardener Samwise Gamgee, Gandalf rides to Isengard to meet with the wizard Saruman but discovers his betrayal and alliance with Sauron, who has dispatched his nine undead Nazgûl servants to find Frodo.

Frodo and Sam are joined by fellow hobbits Merry and Pippin, and they evade the Nazgûl before arriving in Bree, where they are meant to meet Gandalf at the Inn of The Prancing Pony. However, Gandalf never arrives, having been taken prisoner by Saruman. The hobbits are then aided by a Ranger named Strider, who promises to escort them to Rivendell; however, they are ambushed by the Nazgûl on Weathertop, and their leader, the Witch-King, stabs Frodo with a Morgul blade. Arwen, an Elf and Strider's beloved, locates Strider and rescues Frodo, summoning flood-waters that sweep the Nazgûl away. She takes him to Rivendell, where he is healed by the Elves. Frodo meets with Gandalf, who escaped Isengard on a Great Eagle. That night, Strider reunites with Arwen, and they affirm their love for each other.

Learning of Saruman's betrayal from Gandalf and now realising that they are facing threats from both Sauron and Saruman, Arwen's father, Lord Elrond, decides against keeping the Ring in Rivendell. He holds a council of Elves, Men, and Dwarves, also attended by Frodo and Gandalf, that decides the Ring must be destroyed in the fires of Mount Doom. Frodo volunteers to take the Ring, accompanied by Gandalf, Sam, Merry, Pippin, the Elf Legolas, the Dwarf Gimli, Boromir of Gondor, and Strider—who is actually Aragorn, Isildur's heir and the rightful King of Gondor. Bilbo, now living in Rivendell, gives Frodo his sword Sting, and a chainmail shirt made of mithril.

The Company of the Ring makes for the Gap of Rohan, but discover it is being watched by Saruman's spies. They instead set off over the mountain pass of Caradhras, but Saruman summons a storm that forces them to travel through the Mines of Moria, where a tentacled water beast blocks off the entrance with the Company inside, giving them no choice but to journey to the exit on the other end. After finding the Dwarves of Moria dead, the Company is attacked by Orcs and a cave troll. They hold them off but are confronted by Durin's Bane: a Balrog residing within the mines. While the others escape, Gandalf fends off the Balrog and casts it into a vast chasm, but the Balrog drags Gandalf down into the darkness with him. The devastated Company reaches Lothlórien, ruled by the Elf-queen Galadriel, who privately informs Frodo that only he can complete the quest and that one of the Company will try to take the Ring. She also shows him a vision of the future in which Sauron succeeds in enslaving Middle-earth, including the Shire. Meanwhile, Saruman creates an army of Uruk-hai in Isengard to find and destroy the Company.

The Company travels by river to Parth Galen. Frodo wanders off and is confronted by Boromir, who, as Lady Galadriel had warned, tries to take the Ring. Uruk-hai scouts then ambush the Company, attempting to abduct the Hobbits. Boromir breaks free of the Ring's power and protects Merry and Pippin, but the Uruk-Hai leader, Lurtz, mortally wounds Boromir as they abduct the Hobbits. Aragorn arrives and kills Lurtz before comforting Boromir as he dies, promising to help the people of Gondor in the coming conflict. Fearing the Ring will corrupt his friends, Frodo decides to travel to Mordor alone, but allows Sam to come along, recalling his promise to Gandalf to look after him. As Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli set out to rescue Merry and Pippin, Frodo and Sam make their way down the pass of Emyn Muil, journeying on to Mordor.

Cast

[edit]

Before filming began on 11 October 1999, the principal actors trained for six weeks in sword fighting (with Bob Anderson), riding and boating. Jackson hoped such activities would allow the cast to bond so chemistry would be evident on screen as well as getting them used to life in Wellington.[7] They were also trained to pronounce Tolkien's verses properly.[8] After the shoot, the nine cast members playing the Fellowship got a tattoo, the Elvish symbol for the number nine, with the exception of John Rhys-Davies, whose stunt double got the tattoo instead.[9] The film is noted for having an ensemble cast,[10] and some of the cast and their respective characters include:

- Elijah Wood as Frodo Baggins: A young hobbit who inherits the One Ring from his uncle Bilbo. Wood was the first actor to be cast on 7 July 1999.[11] Wood was a fan of the book, and he sent in an audition dressed as Frodo, reading lines from the novel.[12] Wood was selected from 150 actors who auditioned.[13] Jake Gyllenhaal unsuccessfully auditioned for the role after his agency miscommunicated his direction to an American accent.[14]

- Ian McKellen as Gandalf the Grey: An Istari wizard and mentor to Frodo. Sean Connery was approached for the role, but did not understand the plot,[12] while Patrick Stewart turned it down as he disliked the script.[15] Patrick McGoohan was also offered the role, but turned it down due to health issues.[16] Anthony Hopkins and Christopher Plummer also turned down the role.[17][18] Richard Harris expressed interest in the part.[19] John Astin auditioned for Gandalf.[20] Sam Neill was also offered the role but declined due to his scheduling conflict with Jurassic Park III. Before being cast, McKellen had to sort his schedule with 20th Century Fox as there was a two-month overlap with X-Men.[13] He enjoyed playing Gandalf the Grey more than his transformed state in the next two films,[9] and based his accent on Tolkien. Unlike his on-screen character, McKellen did not spend much time with the actors playing the Hobbits; instead he worked with their scale doubles.[7]

- Viggo Mortensen as Aragorn: A Dúnedain ranger and heir to Gondor's throne. Daniel Day-Lewis was offered the part at the beginning of pre-production, but turned it down.[21] Nicolas Cage also received an offer but declined because of family obligations.[22] Stuart Townsend was cast in the role, before being replaced during filming when Jackson realised he was too young.[12] Russell Crowe was considered as a replacement, but he turned it down because he does not want to be typecast and believed to be a similar role in Gladiator.[12] Day-Lewis was offered the role for a second time, but declined again.[21] Executive producer Mark Ordesky saw Mortensen in a play. Mortensen's son, a fan of the book, convinced him to take the role.[7] Mortensen read the book on the plane, received a crash course lesson in fencing from Bob Anderson and began filming the scenes on Weathertop.[23] Mortensen became a hit with the crew by patching up his costume[24] and carrying his "hero" sword around with him off-camera.[7]

- Sean Astin as Samwise Gamgee: Better known as Sam, a hobbit gardener and Frodo's best friend. Astin, who had recently become a father, bonded with the 18-year-old Wood in a protective manner, which mirrored Sam's relationship with Frodo.[7] Before Astin was cast, James Corden read for the part.[25]

- Sean Bean as Boromir: A son of the Stewards of Gondor who journeys with the Fellowship towards Mordor. Bruce Willis, a fan of the book, expressed interest in the role, while Liam Neeson was sent the script, but passed.[12]

- Billy Boyd as Peregrin Took: Better known as Pippin, an extremely foolish hobbit who is a distant cousin of Frodo and travels with the Fellowship on their journey to Mordor.

- Dominic Monaghan as Meriadoc Brandybuck: Better known as Merry, a distant cousin of Frodo. Monaghan was cast as Merry after auditioning for Frodo.[12]

- John Rhys-Davies as Gimli: A dwarf warrior who accompanies the Fellowship to Mordor after they set out from Rivendell. Billy Connolly, who was considered for the part of Gimli, later portrayed Dáin II Ironfoot in Peter Jackson's The Hobbit film trilogy.[12] Rhys-Davies wore heavy prosthetics to play Gimli, which limited his vision, and eventually he developed eczema around his eyes.[7] Rhys-Davies also played Gimli's father Glóin during the scene where the fellowship is forged.

- Orlando Bloom as Legolas: A prince of the elves' Woodland Realm and a skilled archer. Bloom initially auditioned for Faramir, who appears in the second film, a role which went to David Wenham.[12]

- Liv Tyler as Arwen: An elf of Rivendell and Aragorn's lover. The filmmakers approached Tyler after seeing her performance in Plunkett & Macleane, and New Line Cinema leaped at the opportunity of having one Hollywood star in the film. Actress Helena Bonham Carter had expressed interest in the role.[12] Tyler came to shoot on short occasions, unlike the rest of the actors. She was one of the last actors to be cast, on 25 August 1999.[26]

- Cate Blanchett as Galadriel: The elven co-ruler of Lothlórien alongside her husband Celeborn. Lucy Lawless was considered for the role.[27]

- Christopher Lee as Saruman the White: The fallen head of the Istari Order who succumbs to Sauron's will through his use of the palantír. Lee was a major fan of the book, and read it once a year. He had also met J. R. R. Tolkien.[23] He originally auditioned for Gandalf, but was judged too old.[12]

- Hugo Weaving as Elrond: The Elven-Lord of Rivendell and Arwen's father who leads the Council of Elrond, which ultimately decides to destroy the Ring. David Bowie expressed interest in the role, but Jackson stated, "To have a famous, beloved character and a famous star colliding is slightly uncomfortable."[13]

- Ian Holm as Bilbo Baggins: Frodo's uncle who gives him the Ring after he decides to retire to Rivendell. Holm previously played Frodo in a 1981 radio adaption of The Lord of the Rings, and was cast as Bilbo after Jackson remembered his performance.[12] Sylvester McCoy, who later played Radagast the Brown in The Hobbit, was contacted about playing the role, and was kept in place as a potential Bilbo for six months before Jackson went with Holm.[28]

- Andy Serkis as Gollum (voice/motion-capture): A wretched hobbit-like creature whose mind was poisoned by the Ring after bearing it for 500 years. This character appears briefly in the prologue. In Mordor, one can only hear his voice shouting and in Moria, only his eyes and his nose appear. Serkis was working on the 1999 six-episode Oliver Twist miniseries when his agent told him that Jackson wanted to approach him to play Gollum. Despite ultimately accepting the role, Serkis was initially doubtful about taking the part as one of his Oliver Twist fellow actors opined that it was not a good idea if his face was not going to appear onscreen, aside that Jackson was unsure if Gollum could be portrayed with motion-capture performance as they wished.[29]

Comparison to the book

[edit]Jackson, Walsh and Boyens made numerous changes to the story, for purposes of pacing and character development. Jackson said his main desire was to make a film focused primarily on Frodo and the Ring, the "backbone" of the story.[30] The prologue condenses Tolkien's backstory, in which The Last Alliance's seven-year siege of Barad-dûr is a single battle, where Sauron is shown to explode, though Tolkien only said his spirit flees.[31]

Some events and characters from the book are condensed or omitted (as with Tom Bombadil) at the beginning of the film. The time between Gandalf leaving the Ring to Frodo and returning to reveal its inscription, which is 17 years in the book, is compressed for timing reasons.[32] The filmmakers also decided to move the opening scenes of The Two Towers, the Uruk-hai ambush and Boromir's death, to the film's linear climax.[30][32]

The tone of the Moria sequence was altered. In the book, following the defeat on the Caradhras road, Gandalf advocates the Moria road against the resistance of the rest of the Company (save Gimli), suggesting "there is a hope that Moria is still free...there is even a chance that Dwarves are there," though no one seems to think this likely. Frodo proposes they take a company vote, but the discovery of Wargs on their trail forces them to accept Gandalf's proposal. They only realise the Dwarves are all dead once they reach Balin's tomb. The filmmakers chose instead for Gandalf to resist the Moria plan as a foreshadowing device. Gandalf says to Gimli he would prefer not to enter Moria, and Saruman is shown to be aware of Gandalf's hesitance, revealing an illustration of the Balrog in one of his books. The corpses of the dwarves are instantly shown as the Company enter Moria.[33] One detail that critics have commented upon is that, in the novel, Pippin tosses a mere pebble into the well in Moria ("They then hear what sounds like a hammer tapping in the distance"), whereas in the film, he knocks an entire skeleton in ("Next, the skeleton ... falls down the well, also dragging down a chain and bucket. The noise is incredible.").[34][35][36]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Director Peter Jackson began working with Christian Rivers to storyboard the series in August 1997, as well as getting Richard Taylor and Weta Workshop to begin creating his interpretation of Middle-earth.[37] Jackson told them to make Middle-earth as plausible and believable as possible, and to think of it in a historical manner.[38]

In November,[38] Alan Lee and John Howe became the film trilogy's primary conceptual designers, having had previous experience as illustrators for the book and various other tie-ins. Lee worked for the Art Department creating places such as Rivendell, Isengard, Moria, and Lothlórien, giving Art Nouveau and geometry influences to the Elves and Dwarves respectively.[38][39] Though Howe contributed with Bag End and the Argonath,[38][39] he focussed on the design of the characters' armour, having studied it his entire life.[40] Weta and the Art Department continued to design, with Grant Major turning the Art Department's designs into architecture, and Dan Hennah scouting locations.[38] On 1 April 1999, Ngila Dickson joined the crew as costume designer. She and 40 seamstresses created 19,000 costumes, 40 per version for the actor and their doubles, wearing them out for an impression of age.[24]

Filming locations

[edit]Filming took place at many places across New Zealand. For example, the Arrow River, in the Otago region of South Island, stood in for the Ford of Bruinen,[41][42] where Arwen confronts the nine Nazgûl.[43] Below is a list of filming locations, sorted by their order of appearance in the film:[41][42]

| Fictional location |

Specific location in New Zealand |

General area in New Zealand |

|---|---|---|

| Mordor (Prologue) | Whakapapa skifield | Tongariro National Park |

| Hobbiton | Matamata | Waikato |

| Gardens of Isengard | Harcourt Park | Upper Hutt |

| The Shire woods | Otaki Gorge Road | Kāpiti Coast District |

| Bucklebury Ferry | Keeling Farm, Manakau | Horowhenua |

| Forest near Bree | Takaka Hill | Nelson |

| Trollshaws | Waitarere Forest | Horowhenua |

| Flight to the Ford | Tarras | Central Otago |

| Ford of Bruinen | Arrow River, Skippers Canyon | Queenstown and Arrowtown |

| Rivendell | Kaitoke Regional Park | Upper Hutt |

| Eregion | Mount Olympus | Nelson |

| Dead Marshes | Kepler Mire | Southland |

| Dimrill Dale | Lake Alta | The Remarkables |

| Dimrill Dale | Mount Owen | Nelson |

| Lothlórien | Paradise | Glenorchy |

| River Anduin | Upper Waiau River | Fiordland National Park |

| River Anduin | Rangitikei River | Rangitikei District |

| River Anduin | Poets' Corner | Upper Hutt |

| Parth Galen | Paradise | Glenorchy |

| Amon Hen | Mavora Lakes, Paradise and Closeburn | Southern Lakes |

Score

[edit]James Horner turned down the offer to compose the score.[44] The musical score for The Lord of the Rings films was composed by Howard Shore. It was performed by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Voices, The London Oratory School Schola, and the Maori Samoan Choir, and featured several vocal soloists. Shore wrote almost four hours of finalised music for the film (of which just over three hours are used as underscore), featuring a number of non-orchestral instruments, and a large number (49–62) of leitmotifs.

Two original songs, "Aníron" and the end title theme "May It Be", were composed and sung by Enya, who allowed her label, Reprise Records, to release the soundtrack to The Fellowship of the Ring and its two sequels. In addition to these, Shore composed "In Dreams", which was sung by Edward Ross of the London Oratory School Schola.

Release

[edit]Theatrical

[edit]The world premiere of The Fellowship of the Ring was held at the Odeon Leicester Square in London on 10 December 2001. It was released on Wednesday, 19 December 2001 internationally in most major territories on 10,000 screens.[45] It opened in New Zealand on 20 December.

Marketing

[edit]A special featurette trailer was released in April 2000. This trailer was downloaded over 1.7 million times within its first 24 hours of release, breaking Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace's for being the most downloaded trailer.[46] The trilogy sizzle reel was shown before Thirteen Days and the teaser trailer before Pearl Harbor. The theatrical trailer was attached with the television premiere of Angel and before Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. Both trailers appeared as Easter eggs on the Rush Hour 2 and Little Nicky home video releases.

Home media

[edit]Theatrical version

[edit]The theatrical version of The Fellowship of the Ring was released on VHS and DVD on 6 August 2002 by New Line Home Entertainment.[47] It was the best-selling DVD release at the time with 14.5 million copies being sold. This record was dethroned by Finding Nemo the following year.[48]

The Blu-ray edition of the theatrical The Lord of the Rings trilogy was released in the United States on 6 April 2010. There were two separate sets: one with digital copies and one without.[49] The individual Blu-ray disc of The Fellowship of the Ring was released on 14 September 2010 with the same special features as the complete trilogy release, except there was no digital copy.[50]

Extended version

[edit]

On 12 November 2002, an extended edition was released on VHS and DVD, with 30 minutes of new material, added special effects and music, plus 19 minutes of fan-club credits, totalling 228 minutes.[51][52][53] The DVD set included four commentaries and over three hours of supplementary material.

On 29 August 2006, a limited edition of The Fellowship of the Ring was released on DVD. The set included both the film's theatrical and extended editions on a double-sided disc along with all-new bonus material.

The extended Blu-ray editions were released in the US on 28 June 2011.[54] This version has a runtime of 238 minutes,[52][55] with the Blu-ray's additional 10 minutes resulting from lengthier rolls of the fan club members updated at the time of the release, not any additional story material.

The Fellowship of the Ring was released in Ultra HD Blu-ray on 30 November 2020 in the United Kingdom and on 1 December 2020 in the United States, along with the other films of the trilogy, including both the theatrical and the extended editions of the films.[56]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]On its opening day, The Fellowship of the Ring grossed $18.2 million in the United States and Canada from 3,359 cinemas and $11.5 million in 13 countries, including $3 million from 466 screens in the United Kingdom.[3][57] It grossed $75.1 million in its first five days in the United States and Canada, including $47.2 million on its opening weekend, placing it at number one at the US box office, setting a December opening record, beating Ocean's Eleven.[58][3]

The film also opened at number one in 29 international markets and remained there for a second week in all but the Netherlands. It set a record opening day gross in Australia with $2.09 million from 405 screens, beating the record $1.3 million set by Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.[59] It had a record opening weekend in Germany with 1.5 million admissions and in Spain with a gross of $5.3 million from 395 screens. It also grossed a record $2.5 million in 15 days in New Zealand.[60] This record would last for less than a decade before being surpassed by Avatar.[61] In Denmark, it became the country's highest-grossing film, surpassing Titanic.[62] In its first 15 days, the film had grossed $183.5 million internationally and $178.7 million in the United States and Canada for a worldwide total of $362.2 million.[60][3]

In its initial release, it went on to gross $319.2 million in the United States and Canada and $567.3 million in the rest of the world for a worldwide total of $887.2 million.[5] Box Office Mojo estimates that the film sold over 54 million tickets in the US and Canada in its initial theatrical run.[63] Following subsequent reissues, the film has grossed $319.4 million in the United States and Canada and $567.4 million in the rest of the world for a worldwide total of $887.4 million.[3]

Critical response

[edit]On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring holds an approval rating of 92% based on 237 reviews, with an average rating of 8.20/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Full of eye-popping special effects, and featuring a pitch-perfect cast, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring brings J.R.R. Tolkien's classic to vivid life."[64] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 92 out of 100 based on 34 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[65] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[66]

Colin Kennedy for Empire gave the film five stars out of five, writing "Brooking no argument, history should quickly regard Peter Jackson's The Fellowship of the Ring as the first instalment of the best fantasy epic in motion picture history... Putting formula blockbusters to shame, Fellowship is impeccably cast and constructed with both care and passion: this is a labour of love that never feels laboured. Emotional range and character depth ultimately take us beyond genre limitations..."[67] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three out of four stars and stating that while it is not "a true visualization of Tolkien's Middle-earth", it is "a work for, and of, our times. It will be embraced, I suspect, by many Tolkien fans and will take on aspects of a cult. It is a candidate for many Oscars. It is an awesome production in its daring and breadth, and there are small touches that are just right".[68] USA Today also gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, "this movie version of a beloved book should please devotees as well as the uninitiated".[69] In his review for The New York Times, Elvis Mitchell wrote, "The playful spookiness of Mr. Jackson's direction provides a lively, light touch, a gesture that doesn't normally come to mind when Tolkien's name is mentioned".[70] Lisa Schwarzbaum for Entertainment Weekly gave the film an A grade and wrote "The cast take to their roles with becoming modesty, certainly, but Jackson also makes it easy for them: His Fellowship flows, never lingering for the sake of admiring its own beauty ... Every detail of which engrossed me. I may have never turned a page of Tolkien, but I know enchantment when I see it".[71] In his review for the BBC, Nev Pierce gave the film four stars out of five, describing it as "Funny, scary, and totally involving", and wrote that Jackson turned "the book's least screen-worthy volume into a gripping and powerful adventure movie".[72] In his review for The Guardian, Xan Brooks wrote "Rather than a stand-alone holiday blockbuster, The Fellowship of the Ring offers an epic act one", and commented that the ending was "closer in spirit to an art-house film than a popcorn holiday romp".[73]

In her review for The Washington Post, Rita Kempley gave the film five stars out of five, and praised the cast, in particular, "Mortensen, as Strider, is a revelation, not to mention downright gorgeous. And McKellen, carrying the burden of thousands of years' worth of the fight against evil, is positively Merlinesque".[74] Time magazine's Richard Corliss praised Jackson's work: "His movie achieves what the best fairy tales do: the creation of an alternate world, plausible and persuasive, where the young — and not only the young — can lose themselves. And perhaps, in identifying with the little Hobbit that could, find their better selves".[75] In his review for The Village Voice, J. Hoberman wrote, "Peter Jackson's adaptation is certainly successful on its own terms".[76] Rolling Stone magazine's Peter Travers wrote, "It's emotion that makes Fellowship stick hard in the memory... Jackson deserves to revel in his success. He's made a three-hour film that leaves you wanting more".[77] A mixed review was written by Peter Bradshaw. Writing for The Guardian, he lauded the art direction and the visual look of the film, but he also commented "there is a strange paucity of plot complication, an absence of anything unfolding, all the more disconcerting because of the clotted and indigestible mythic back story that we have to wade through before anything happens at all". Overall, Bradshaw found the tone of the film too serious and self-important, and wrote "signing up to the movie's whole hobbity-elvish universe requires a leap of faith... It's a leap I didn't feel much like making – and, with two more movie episodes like this on the way, the credibility gap looks wider than ever."[78] Jonathan Rosenbaum was also less positive about The Fellowship of the Ring: in his review for the Chicago Reader, he granted that the film was "full of scenic splendors with a fine sense of scale", but he commented that its narrative thrust seemed "relatively pro forma", and that he found the battle scenes boring.[79]

Accolades

[edit]In 2002, the film won four Academy Awards from thirteen nominations.[80] It won the 2002 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation. It won Empire readers' Best Film award, as well as five BAFTAs, including Best Film, the David Lean Award for Best Direction, the Audience Award (voted for by the public), Best Special Effects, and Best Make-up. The film was nominated for an MTV Movie Award for Best Fight between Gandalf and Saruman.

In June 2008, AFI revealed its "10 Top 10"—the ten best films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. The Fellowship of the Ring was acknowledged as the second best film in the fantasy genre.[81][82]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ "The Lord Of The Rings - The Fellowship Of The Ring". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ a b "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ a b "2001 Worldwide Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (14 December 2021). "National Film Registry Adds Return Of The Jedi, Fellowship Of The Ring, Strangers On A Train, Sounder, WALL-E & More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f The Fellowship of the Cast (DVD). New Line Cinema. 2002.

- ^ Sibley, Brian (2001). The Lord of the Rings: Official Movie Guide. HarperCollins. pp. 100–101. ISBN 0-00-711908-9.

- ^ a b Sibley, Brian (2006). "Ring-Master". Peter Jackson: A Film-maker's Journey. London: HarperCollins. pp. 445–519. ISBN 0-00-717558-2.

- ^ Clinton, Paul (18 December 2001). "Review: Dazzling, flawless 'Rings' a classic". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ^ "Official Frodo Press Release!". The One Ring.net. 9 July 1999. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sibley, Brian (2006). "Three-Ring Circus". Peter Jackson: A Film-maker's Journey. London: HarperCollins. pp. 388–444. ISBN 0-00-717558-2.

- ^ a b c Flynn, Gillian (16 November 2001). "Ring Masters". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 25 November 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- ^ "How Jake Gyllenhaal flubbed his 'Lord of the Rings' audition". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "New York Con Reports, Pictures and Video". TrekMovie.com. 9 March 2008. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ^ "Obituary: Patrick McGoohan". 14 January 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "Christopher Plummer Turned Down The Role Of Gandalf" – via conanclassic.com.

- ^ Lang, Brent (7 September 2023). "Ian McKellen on Not Retiring, Not Being the First Choice for Gandalf and Going Evil for 'The Critic': 'The Devil Has the Best Lines'". Variety. Archived from the original on 17 October 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Gandalf Vs Dumbledore - Sir Ian Mckellen Discusses Disagreement With Richard Harris". Contact Music. 8 January 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Addams Family star John Astin on Peter Jackson, Fellini, and more". The A.V. Club. 10 May 2022. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ a b xoanon (15 October 1999). "Daniel Day-Lewis Offered role of Aragorn, Again!". theonering.net. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Carroll, Larry (7 December 2007). "Will Smith Snagged 'I Am Legend' From Schwarzenegger, But Can You Imagine Nicolas Cage In 'The Matrix'?". MTV. Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ a b Cameras in Middle-earth: Filming The Fellowship of the Ring (DVD). New Line Cinema. 2002.

- ^ a b Costume Design (DVD). New Line Cinema. 2002.

- ^ "James Corden Auditioned for 'Lord of the Rings' to Play Samwise, Says He Got Two Callbacks: It Was 'Not Good'". 29 December 2022. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Liv Tyler will be in LOTR – Updated". TheOneRing.net. 25 August 1999. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ "Lucy Lawless – Hotcelebs Magazine". Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Parkes, Diane (19 September 2008). "Who's that playing The Mikado?". Birmingham Mail. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Josh Gad (31 May 2020). "One Zoom to Rule Them All | Reunited Apart Lord of the Rings Edition" – via YouTube.

- ^ a b From Book to Screen (DVD). New Line Cinema. 2002.

- ^ Tolkien, J.R.R. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-05699-6.

- ^ a b Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens (2002). Director/Writers Commentary. New Line Cinema (DVD).

- ^ Doman, Rejina (7 January 2008). "Can Hollywood Be Restrained?". Hollywood Jesus. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ "The Fellowship of the Ring". The One Ring: The Home of Tolkien Online. 2001. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ Croft, Janet Brennan (2003). "The Mines of Moria: Anticipation and Flattening in Peter Jackson's The Fellowship of the Ring". Presented at the Southwest/Texas Popular Culture Association Conference. Archived from the original on 31 October 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ Porter, Lynnette R. (2005). Unsung Heroes of The Lord of the Rings: From the Page to the Screen. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. p. 71. ISBN 0-275-98521-0.

- ^ Russell, Gary (2003). The Art of the Two Towers. HarperCollins. p. 8. ISBN 0-00-713564-5.

- ^ a b c d e Designing Middle-earth (DVD). New Line Cinema. 2002.

- ^ a b Big-atures (DVD). New Line Cinema. 2002.

- ^ Sibley (2001), p.90

- ^ a b c "The Lord of the Rings Trilogy filming locations". newzealand.com/us. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ a b "15 LOTR Locations In New Zealand". Huffington Post. 19 September 2015. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. p. 413. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ "R.I.P. James Horner". The A.V. Club. 23 June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Nathan, Ian (April 2021). "The World Is Changed". Empire. p. 65.

- ^ "'Rings' Fans Fuel Download Record".

- ^ "Kia Reaches for the Gold 'Ring'". hive4media.com. 4 June 2002. Archived from the original on 16 June 2002. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Susman, Gary (19 November 2003). "Nemo is already top-selling DVD ever". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings: The Motion Picture Trilogy Blu-ray: Theatrical Editions". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Calogne, Juan (23 June 2010). "Lord of the Rings Movies Get Separate Blu-ray editions". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "THE LORD OF THE RINGS – THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. 16 July 2002. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ a b "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". movies.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Bennett, Dan (17 August 2002). "Lord of the Rings Will Sing a New Tune". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2002. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "Lord of the Rings Pre-order Now Available". Amazon.com. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 30 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". IMDb.com. 19 December 2001. Archived from the original on 28 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ Brew, Simon (9 October 2020). "Lord Of The Rings and The Hobbit set for 4K release in November". filmstories.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Boland, Michaela (24 December 2001). "'Rings' tolls in bright B.O. day o'seas". Variety. p. 9.

- ^ "'Lord of the Rings' rules holiday weekend". News-Journal. 27 December 2001. p. 2. Archived from the original on 18 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Boland, Michaela (1 January 2002). "'Rings' lordly o'seas with $156 mil". Variety. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ a b Boland, Michaela (7 January 2002). "'Lord' runs rings 'round o'seas B.O.". Variety. p. 15.

- ^ Rutledge, Daniel (2 November 2010). "Avatar becomes NZ's highest grossing film ever". Newshub. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ "Lord Of The Rings sinks Titanic in Denmark".

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Cinemascore". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ "Lord Of The Rings: The Fellowship Of The Ring". Empire. January 2001. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (19 December 2001). "Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 27 July 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (18 December 2001). "Middle-earth leaps to life in enchanting, violent film". USA Today. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (19 December 2001). "Hit the Road, Middle-Earth Gang". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (5 December 2001). "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ "BBC – Films – review – The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ "Film review: 'Like an Anglo-Saxon cousin to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon'". The Guardian. 10 December 2001. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (19 December 2001). "Frodo Lives! A Spirited Lord of the Rings". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (17 December 2001). "Lord of the Films". Time. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Hoberman, J (18 December 2001). "Plastic Fantastic". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Travers, Peter (17 January 2002). "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (14 December 2001). "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (17 December 2001). "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "The 74th Academy Awards (2002) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ American Film Institute (17 June 2008). "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ "Top 10 Fantasy". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring at IMDb

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring at AllMovie

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring at Box Office Mojo

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring at Metacritic

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring at Rotten Tomatoes

- 2001 films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s British films

- 2000s children's fantasy films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2001 fantasy films

- American epic fantasy films

- American fantasy adventure films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- English-language fantasy films

- Films about curses

- Films about dwarfs

- Films about legendary creatures

- Films directed by Peter Jackson

- Films produced by Barrie M. Osborne

- Films produced by Fran Walsh

- Films produced by Peter Jackson

- Films produced by Tim Sanders (filmmaker)

- Films scored by Howard Shore

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in New Zealand

- Films that won the Academy Award for Best Makeup

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Visual Effects Academy Award

- Films using motion capture

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Direction BAFTA Award

- Films with screenplays by Fran Walsh

- Films with screenplays by Peter Jackson

- Films with screenplays by Philippa Boyens

- High fantasy films

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation–winning works

- The Lord of the Rings (film series)

- Middle-earth (film franchise) films

- Nebula Award for Best Script–winning works

- New Line Cinema films

- New Zealand epic films

- New Zealand fantasy adventure films

- Saturn Award–winning films

- United States National Film Registry films

- WingNut Films films